Housing people, not diseases in the face of COVID-19

As cities lockdown to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, liveability and thermal comfort of houses of all income classes have hogged attention. While trapped stale air in ill-designed thermally uncomfortable air-conditioned houses can foster infectious diseases, overcrowding in lower-income households with no ventilation creates more risks for the urban poor. The current public health emergency has reinforced the fact that housing sector policy and interventions will have to change in the post-pandemic period for healthy living.

This has emerged from the recent analysis of the housing sector carried out by CSE. Lessons drawn from the ongoing implementation of affordable housing programs like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for urban areas(PMAY-U) and from the reviews of the design and performance of affordable housing units at the state level have been captured in this new policy brief — Beyond the Four Walls of PMAY: Resource efficiency, thermal comfort and liveability in the affordable housing sector.

The verticals of the PMAY-U program represent different types of housing provision approaches, including affordable housing delivered by state governments in partnership with the private sector;beneficiary-led construction or self-construction; credit-led housing; and in-situ slum development. The experiences with each of these have thrown up several lessons that are relevant for the pandemic and post-pandemic phases. This reinforces the need for designing buildings and neighborhoods for liveability, thermal comfort, and resource efficiency.

This pandemic, for instance, has raised huge concerns around the potential risk in mechanically cooled buildings. Scientists have said that even if a high summer outdoor temperature does manage to diminish the virus, mechanically cooled indoor temperatures and the air ducts of centrally air-conditioned buildings may enable the virus to thrive. In fact, anticipating risk, the COVID-19 Task Force and the Indian Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning (ISHRAE) have even released a guideline booklet that recommends maintaining reasonably high levels of humidity, high rate of air change, and higher air temperature, among other things.

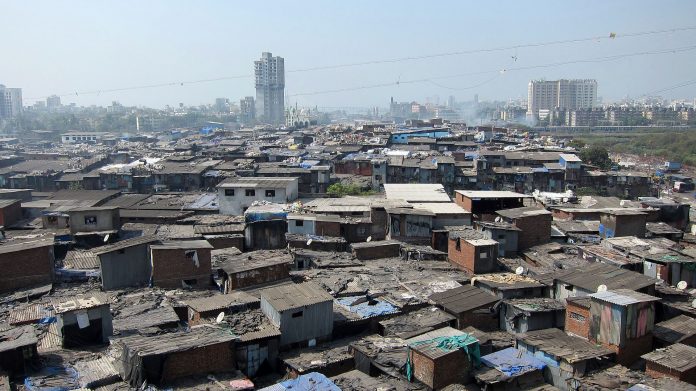

At the same time, social distancing, which is needed to stay safe, is virtually impossible in the poorly designed small spaces in housing units of low-income groups. The migrant crisis has also shown how current approaches to housing provisions for the poorer sections need to change. Moreover, the overall hygiene of neighborhoods in terms of access to water, sanitation, and waste management requires most decentralized and efficient municipal services and decentralized resource and waste management systems to control the exposure to risk. Access to a clean environment will have to be universal to protect all.

What is at stake?

Achieving liveability goals while addressing the housing crisis: India has to achieve the goals of health and liveability and thermal comfort within the current housing crisis. While the latest estimates of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) puts the national housing demand at 11.2 million (lowered from 20 million five years ago), unofficial estimates report a higher housing demand. Also consider the fact that close to 14 million households live in urban slums under unliveable conditions. According to the Census of 2011, India is adding around four million people to its slums every year.

In current times of social distancing, crowded dwellings can be a bigger threat to health. The Technical Group on Urban Housing Shortage has estimated that around 80 percent of the nation’s housing demand comes from congestion or overcrowding in houses. A house is defined overcrowded in India when a married couple does not have a separate room. To this is added homelessness, building rejection, and non-serviceability of buildings.While standardizing, the criteria for housing demand assessment include health and liveability criteria to ensure access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing.

Formal affordable housing must be designed for liveability, thermal comfort, and resource efficiency: The current concern over thermally uncomfortable building, which increases air-conditioning usage and the risk of infections, has once again brought to the forefront the need to design buildings for thermal comfort and to minimize air-conditioned hours. Out of the total approved projects under PMAY-U, 34 percent are under the ‘Affordable Housing in Partnership’ that the private sector is delivering (with support from the government). But nearly the entire focus is on speed and ease of construction and material choices. It is now necessary to link these subsidies and incentives with the performance of the housing stock to ensure quality and liveability of the houses.

India’s Cooling Action Plan has categorically stated the goal of ‘thermal comfort for all’. This needs to be integrated with the requirement of affordable housing. While planning for improved energy efficiency in buildings, it is also important to target for improved thermal comfort through material choices, designs, and orientation. Thermal comfort is defined by parameters like temperature, ventilation, and relative humidity in India as per the National Building Code (NBC). Interestingly, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines the same parameters for healthy housing.

To demonstrate, CSE has simulated sample PMAY-U housing for thermal comfort and day-lighting according to the NBC and evaluated energy performances with respect to Eco Niwas Samhita. The study found that dwelling units in existing designs can achieve thermal comfort for a minimum of 74 percent of the period annually to a maximum of 85 percent in the native climate. Similarly, daylight analysis showed that the day-lit area is 47 percent of the total living area when other buildings are not shading the specific building. Where the buildings are mutually shading each other, the day-lit area is only 15 percent.

How can the poor self-construct for healthy living: The most striking aspects of the PMAY-U is that the vertical of ‘Beneficiary-led Construction’ or self-construction by lower-income households who build incrementally in plotted housing has got the maximum approval of projects — 63 percent of all houses under PMAY-U. This needs a strategy to inform and enable this group to adopt thermal comfort criteria in terms of materials, designs, and appropriate energy management. Currently, voluntary groups and non-governmental organizations are extending this support.

From the perspective of sustainability and liveability, housing projects will have to consider a whole gamut of criteria: at the level of building typology and design — thermal comfort, resource efficiency and common services related to water, energy and waste; and at the neighborhood level — locational aspects, connectivity and urban greens.

Addressing liveability and sustainability in the affordable housing sector: There are some mandatory requirements under PMAY-U that, if addressed properly, can take care of the liveability aspects of projects. One such condition is earmarking land for affordable-housing in master plans. This is an important condition as it allows an assessment of the suitability of locations from usability and liveability perspectives. But this opportunity is compromised simply by the fact that currently, 76.2 percent of the 7,953 census towns in India do not have a master plan.

Decentralization of services: The marginalized and poor are the ones who are deprived of safe water, sanitation, and solid waste management and are most valuable to the disease. The CSE review finds that environmental services are not being implemented in the new housing stock to meet their spirit and function, despite a number of supporting incentives and mandates.

Rental housing gap in the PMAY-U: At present, there is no provision for rental housing under PMAY-U. But there is an enormous demand for this kind of housing. A draft National Urban Rental Housing Policy, 2015 exists and needs to be improved on and implemented. This is needed to keep housing within the affordability of the range of the target groups – a large section of this is the floating migrant population.

The way forward

Currently, state governments are focusing on producing voluminous stocks of buildings at speed with construction techniques that enable governments to meet their targets by 2022. This approach risks the creation of underperforming assets and infrastructure that may not fulfill the target of providing quality and liveable shelters to low-income groups. It is important that for the next phase of PMAY-U and state-level housing interventions towards augmentation of housing supply, immediate steps are taken to combine the criteria of thermal comfort, livability, and healthy living for all.

- Standardize criteria for estimating housing shortage and include health criteria to define congestion.

- Introduce more comprehensive guidelines and mandates on material and architectural design to improve the thermal comfort of buildings and reduce air-conditioned hours for energy savings and healthy living.

- Introduce guidelines for mass housing in terms of fixing orientation to improve solar access, adopting compact urban form with adequate green spaces, and also for ventilation and mutual shading.

- Earmark locations in Master Plan to improve locational advantages of affordable housing to reduce the economic and social costs of living. Plan the building and its habitat together.

- Implement decentralized services related to water access, rainwater harvesting, sanitation and segregated waste management to improve health and well-being.

- Build accessible technical knowledge support and professional help for beneficiary-led self-construction to enable people to build well-ventilated and well-lit healthy spaces with thermal comfort. Ensure appropriate skill-building to cater to this requirement.

By Ms. Pratyusha Mukherjee, an active Journalist working for BBC and other media outlets, also a special contributor to IBG News & IBG NEWS BANGLA. In her illustrated career she has covered many major events.